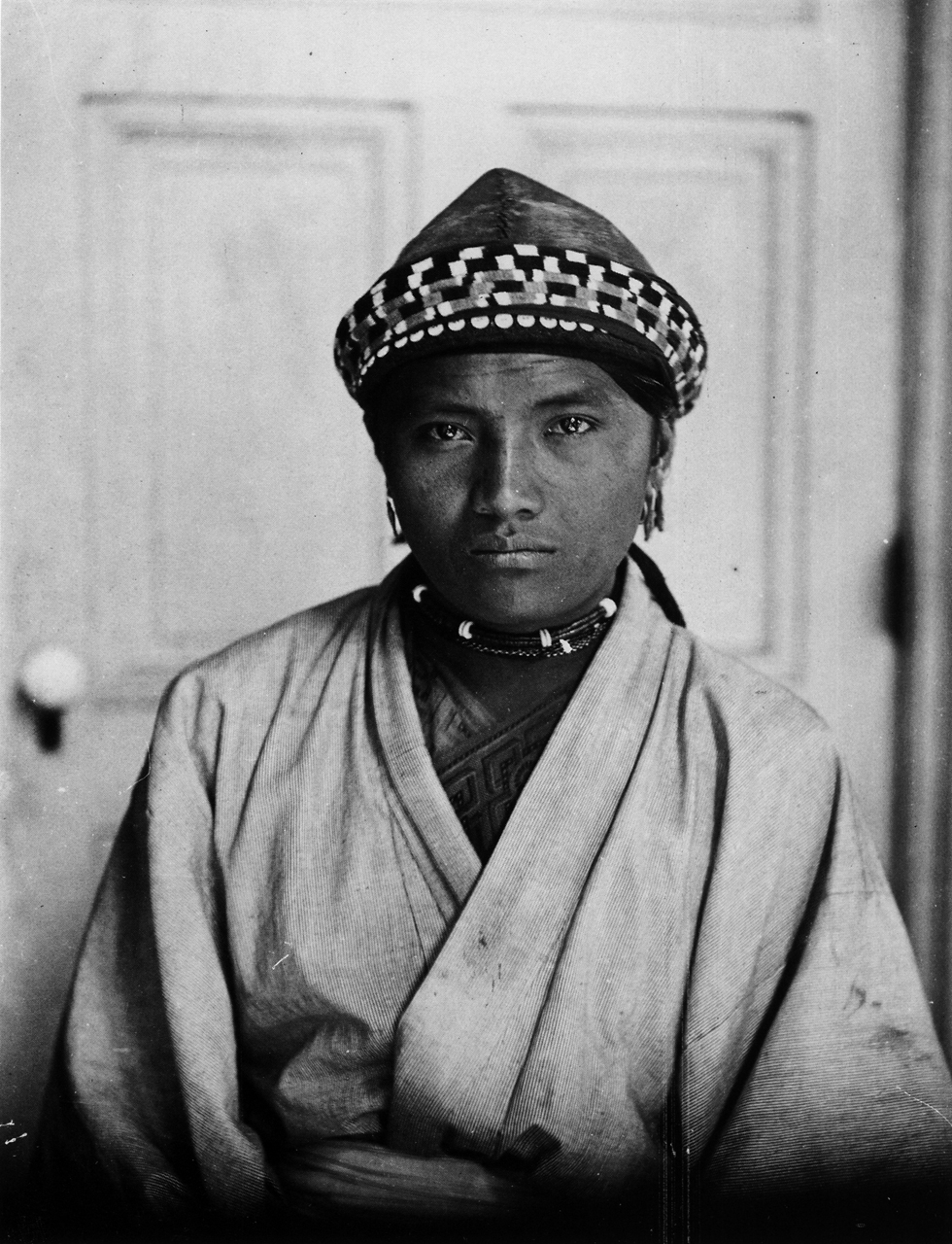

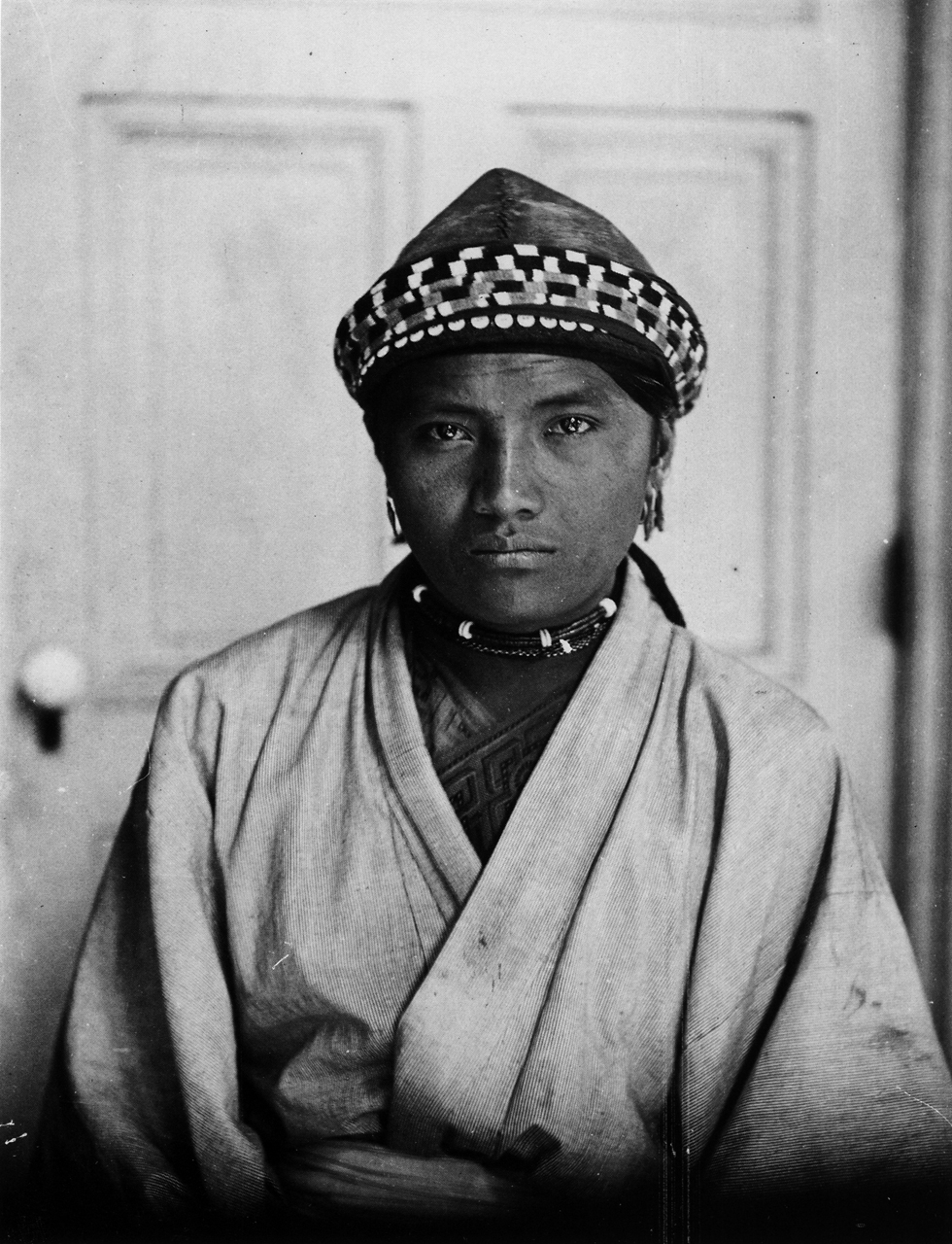

Rukai Chief Visiting the Department of Anthropology

at Tokyo’s Imperial University, 1900.

Source: Wikipedia.

Taiwan’s First Peoples

The first humans appeared in Taiwan between 30,000 and 50,000 years ago. Taiwan’s indigenous people are considered to be of Austronesian lineage, and belong to the same language family as those in Southeast Asia, Oceania and Madagascar. They arrived in Taiwan at different times and settled primarily in the plains and in the mountains.

Taiwan’s indigenous people enjoyed total sovereignty and lived independently for many thousands of years before the island was invaded by foreigners in the 17th century. The first to arrive were the Dutch, who occupied Taiwan for 28 years beginning in 1624. They were followed by the Spanish, Portuguese, and Han Chinese during the Ming and Qing dynasties. This was followed by Japanese occupation from 1895 to 1945 and finally by the Nationalist Chinese, who settled in Taiwan in 1949-50 after losing China to the Communists.

Indigenous Taiwanese did not welcome foreign invaders with open arms. The Dutch, Spanish, Portuguese and Chinese only controlled limited parts of Taiwan, avoiding the wrath of indigenous groups, many of which were fierce fighters. Beheadings were common. According to McCulloch’s Universal Gazetteer (1846) speaking of military control from 1643: “The authority of China has been ever since maintained over the island, though assailed by repeated insurrections.” These problems did not involve indigenous Taiwanese alone, but were due to Han Chinese settlers who emigrated from Fujian during the late Ming and early Qing dynasties: McCulloch described them as “…a laborious and industrious race, well-disposed towards foreigners, but very turbulent in respect to the home authorities, who maintain only a very precarious sway over them. The Formosans having frequently risen in open rebellion against their mother country.” The Gazetteer added: “The Chinese garrison in Tae-wan [the former capital; now Tainan], amounts to about 10,000 men; the total armed forces usually stationed on the island may be estimated at almost double that number, all infantry.”

Shortly after Taiwan was ceded to Japan by Imperial China after the First Sino-Japanese War, the new colonial government initiated a bloody five-year military campaign to subdue the tribes. It was not an easy process: at one point, Japanese diplomats even began negotiations with the French to purchase the island from Japan.

Although there was ongoing Japanese oppression of indigenous groups throughout Taiwan, the Truku and Japanese War of 1914 was especially devastating. The Truku people lived in what is now Hualien County in eastern Taiwan, and they strongly resisted Japanese occupation of their native lands. During this war, some 3000 Truku warriors fought against 20,000 well-armed Japanese troops, suffering huge losses. Eventually Truku elders decided to surrender to the Japanese military in order to prevent the obliteration of their tribe. As a consequence of the war, many of the surviving members of the Truku tribe were moved in groups from the mountains to the plains, and were scattered to many different locations. By taking this action, the Japanese hoped to undermine the Truku's traditional social structure, culture and beliefs.

The Japanese Imperial government also forced the relocation of other indigenous mountain people to the lowlands and scattered communities from the same tribe in order to make them live far apart from each other. The forced relocation made it easier for the Japanese government to control the indigenous population. It also caused many indigenous groups to abandon traditional hunting and gathering practices and take up farming in order to survive.

After the Japanese left Taiwan in 1945, many indigenous Taiwanese breathed a sigh of relief. But when the Chinese Nationalist Party set up the Republic of China in Taiwan in 1949, they continued the Japanese campaign to “civilize” Taiwan’s indigenous people. Like the Native Americans who were often depicted as cruel and degenerate by the white majority in the United States, Taiwanese children were taught that the original inhabitants of Taiwan were uncivilized savages to be looked down upon. Indigenous Taiwanese were not allowed to speak their native languages in public, and their concerns regarding human rights were either minimized or ignored by the government. Many Taiwanese of Chinese ancestry considered them to be second-class citizens.

Young Amis women in ceremonial dress.

From A Pocket Guide to Taiwan.

United States Department of Defense, 1958.Today

The indigenous peoples of Taiwan today consist of fourteen officially recognized tribes, as well as several that are unrecognized, totaling nearly 500,000 people. This represents just over two percent of the total population of Taiwan, with the rest largely comprised of Han Chinese, who began migrating to Taiwan in the late 1600s. The officially recognized tribes are: Amis, Atayal, Bunun, Kavalan, Paiwan, Puyuma, Rukai, Saisiyat, Sakizaya, Sediq, Thao, Truku, Tsou, and Yami. Despite centuries of colonization and assimilation policies, seventeen indigenous languages are spoken in Taiwan today, a proud testament to the resiliency of Taiwan’s indigenous peoples.

Since the late 1980s, the Taiwanese government has sought to respect indigenous peoples and strengthen their cultural identity. Indigenous languages are being taught in schools, native lands are being protected, and traditional dance, art and ceremonial practices are being promoted. President Tsai Ing-wen, whose paternal grandmother was of Paiwan descent, has been especially sensitive to the needs of Taiwan’s indigenous peoples. Still, the hopes of many indigenous leaders regarding a variety of issues — such as the allocation of indigenous names, tribal autonomy, hunting rights and land rights (some native lands are being marked for use as national parks) still have a way to go.

Traditional festival, Maoli.

Photo by Nathaniel Altman

Notes

McCulloch’s Universal Gazetteer (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1846).

Chou, Wan-yao. An Illustrated History of Taiwan (Taipei: SMC Publishing Inc., 2010).

“Realising Taiwan’s indigenous potential,” https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2021/09/08/realising-taiwans-indigenous-potential/

© 2022 by Nathaniel Altman